My friend Hirooki is an undergrad History major at my school. He is also an avid rock climber. He walks around campus with a hiking backpack with all sorts of climbing gear attached to his bag. One day, I asked him why he carried so much equipment. “I always like to be ready to climb,” he replied.

The other day, he took me indoor climbing at The Spot Bouldering Gym in Boulder, Colorado.

Actually, no. I took him there.

I drove because he has no car. In exchange, he agreed to give me a one-day lesson on climbing.

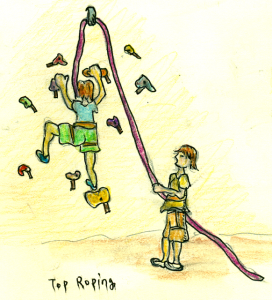

On the car ride from Greeley to Boulder, he described to me the basics of climbing. I learned that there are different types of climbing (bouldering, top-roping, and lead-climbing).

Bouldering

Top Roping

Lead Climbing

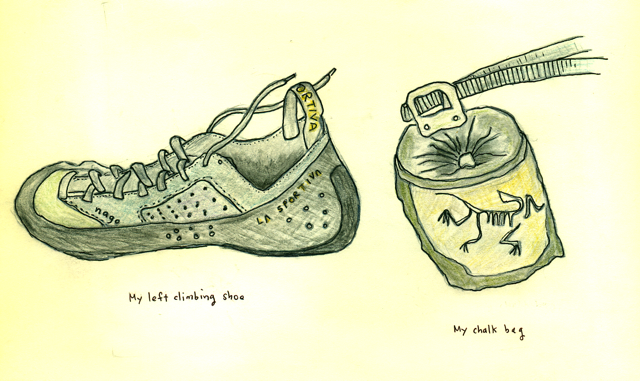

There is also indoor and outdoor climbing. In addition there are all sorts of tools and equipment that is used when climbing, depending on the place and type of climbing. That day, I would be bouldering, so I just needed special rubber soled climbing shoes and a chalk bag for my sweaty hands.

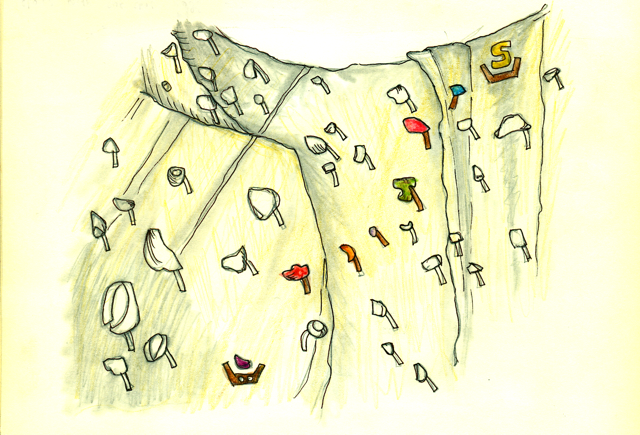

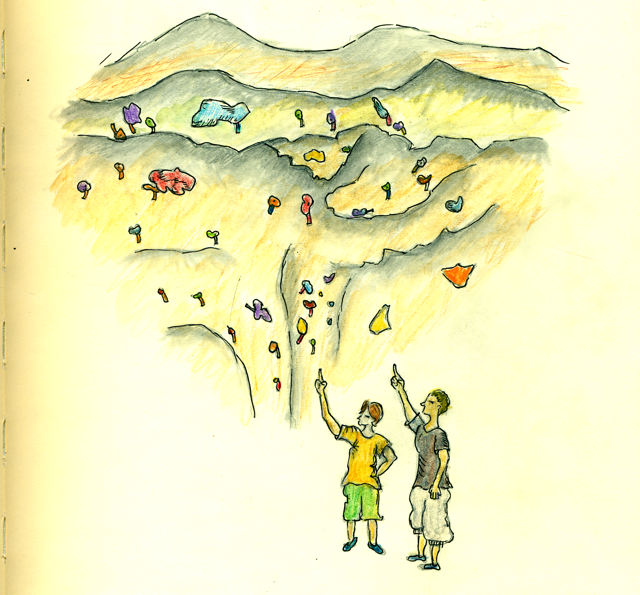

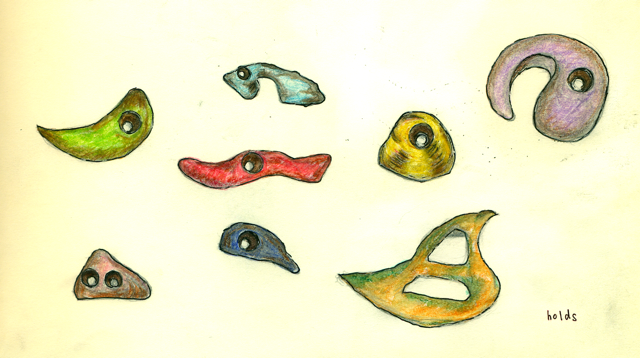

In indoor climbing, there is usually an artificial wall with a bunch of colorful “holds” drilled onto the wall.

When you approach a wall for the first time, climbing looks terribly complicated. First, the wall is extremely tall: 25ft (It actually looks taller).

Also, there are so many colorful holds in all shapes and sizes. It’s hard to figure out what you’re supposed to do. On top of that, some parts of the wall are angled, so it looks like you will most likely fall. I hate the feeling of falling.

Hirooki assured me that it wasn’t very difficult. The idea is to use your hands and feet (and other body parts if necessary) to climb to the top of the designated route. The routes are color-coded based on difficulty. At the Spot, the levels range from one spot to 5+ spots with 1 spot being the easiest. I picked a 2 spot route where each of the holds relevant to the route were tagged with brown tape.

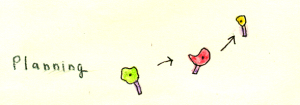

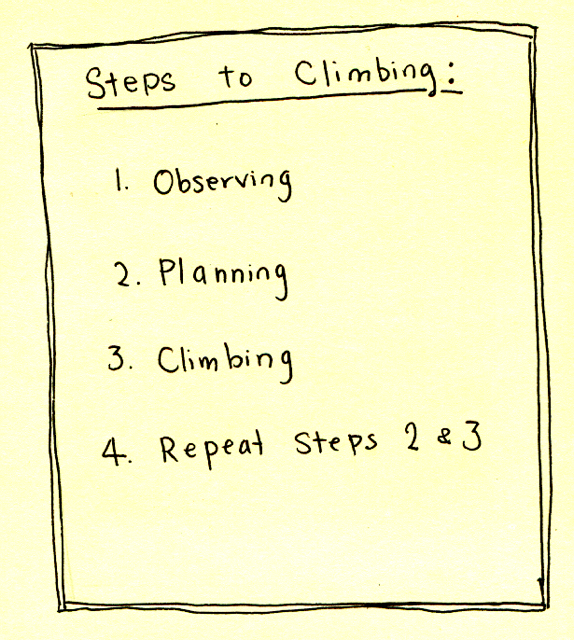

According to Hirooki, there are three main steps to rock climbing: observing, planning, and climbing. (Of course this is simplified greatly).

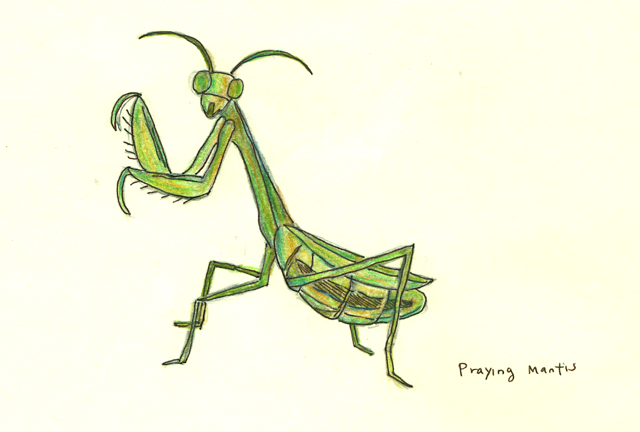

First you have to take a look at the route. Because everything is tagged, you have to know where you are going and which holds you are allowed to use to get to the top of the wall. In my case, I could only use my hands and feet on the holds tagged with brown tape. The problem is, once you start climbing, because the tape is underneath the hold, you can’t see it very well. You have to figure out where you need to go in advance. Hence, step number 2: planning. When I watched Hirooki plan his route, he was deep in thought, moving his hands and feet. He kind of looked like a praying mantis.

Once that is figured out, the last step is to climb: The fun part.

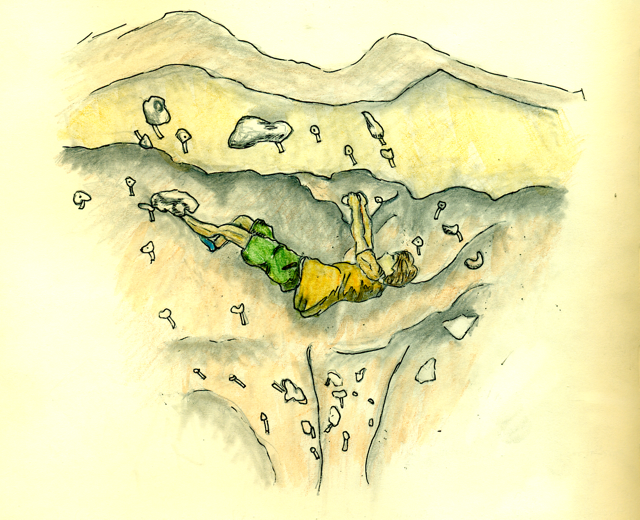

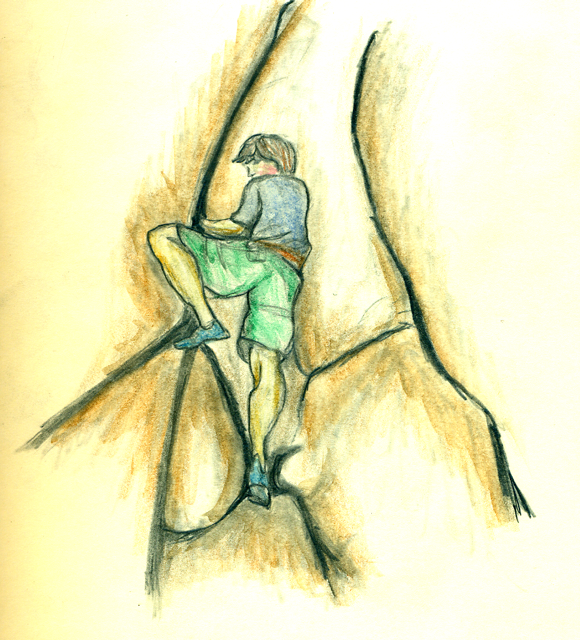

Hirooki attempted a very difficult route (I think it was 4+ or 5 spots).

He made all sorts of screaming and grunting sounds as he pushed himself upward and sideways and underneath different holds. It was quite amazing seeing a person stay attached to a wall that was at such a steep angle. Eventually he fell onto a crash pad. He tried this a number of times; each time, he would reach a certain hold and fall: “FUCK!” The crowd, which had begun to gather around him in amazement, clapped for his effort.

Unperturbed, he came and sat next to me to rest. Within seconds, he was planning his next attempt, soaking his hand in his chalk bag.

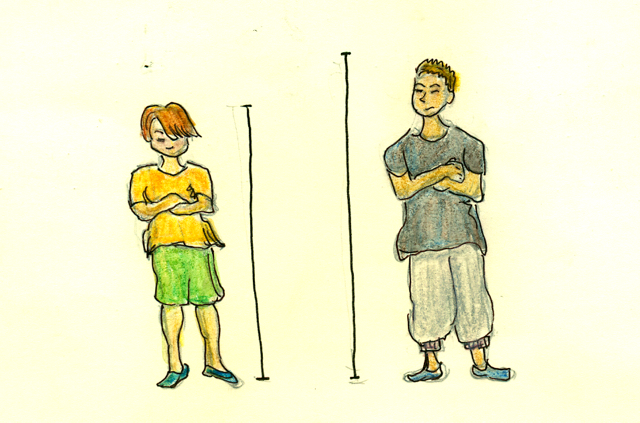

Along came another climber attempting the same route. This guy was a lot taller than Hirooki and had a larger frame.

He could grab holds that were further away, but eventually, he too, fell. Hirooki whispered to me, “See that hold up there?” pointing at a small maroon hold. “There is a small hole at the top. He probably can’t put his finger in it, but I have smaller fingers. I can grasp it better. You shouldn’t be deceived by body size.” He jumped up. It was now his turn.

After falling again, Hirooki went to the other guy, and I saw them discussing the best strategy for the route.

After a number of unsuccessful attempts, Hirooki smiled, “This was so much fun. Let’s go practice some of your routes.” For the remainder of the day, he gave me practical advice on my climbing.

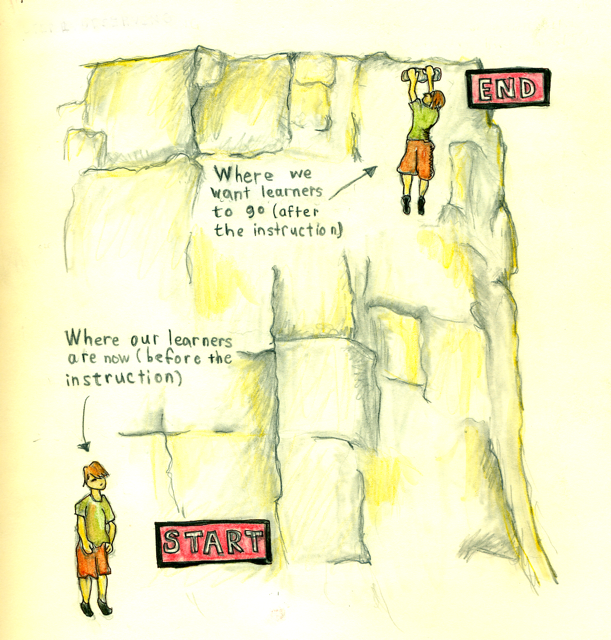

After the experience, I realized that climbing is a lot like instructional design (ID). In ID, there is a big problem (the wall) that we want our learners to solve.

I guess for behaviorists, the bottom of the wall is where the learner is, currently. The top of the wall is where we want the students to end up. The in-between is the “gap”. I think this is a lot like doing a needs assessment and writing performance objectives.

In ID, we observe the situation (through learner analysis, content analysis, goal analysis, etc). As instructional designers, we have to create an instructional problem that is solvable based on the learner’s current knowledge and abilities. This means we have to observe where the end is, while considering the learner and their capabilities and make assumptions about how they will learn.

Next comes the planning phase. As instructional designers, we figure out how to best get to the top of the wall (through coming up with strategies and message design). Of course, we can choose a “one-spot” problem or a “five-spot” problem based on the learner analysis. It will get to the same top-of-the wall, but some are easier to solve than others. For example, if I attempted a 5 spot problem from the start, I wouldn’t even be able to get to the second hold. This would be ineffective, inefficient, and honestly not fun for me as a learner. In ID-speak, this would be considered extraneous load.

The last step of climbing is very similar to the implementation phase of instructional design.

Essentially, we do it. If they can do it, great. If not, we make changes to the design.

For behaviorists, the main goal is to get to the top of the wall. We know the learner has demonstrated competence if they have reached the top of the wall. This makes sense. So we should get to the top of the wall. That’s the point of climbing. Right?

Not necessarily.

After Hirooki coached me until exhaustion (my arms felt like they were made of rubber), he attempted one last chance at that difficult route.

“FUCK!”

He walked toward me, smiling again. “I’m tired. Let’s go eat.” We decided to leave and get dinner at Wahoos! Yes! Fish tacos!

During dinner, I asked Hirooki if he didn’t want to keep on trying the route until he got to the top. His answer surprised me. “I’m exhausted for the day. Plus, getting to the top is nice, but I learned a lot. It was a lot of fun.”

Surprised by his answer, I asked him to elaborate on his “learning”.

“Climbing a route is like trying to solve a problem. There is more than one way to get to the answer. Each time I fall, I learn more about different ways to adjust my body or the muscles in my fingers. You’ll be surprised to learn about all the different muscles that you have that you didn’t know about. The route is clearly marked, so that doesn’t change for all of us. But depending on your body size and fitness level, you may approach it differently. Maybe you don’t use all the holds. What’s most important is finding and refining your own skills so you can plan and tackle your next step more efficiently.”

He described to me how competitions work in climbing. In competitive climbing, climbers are given points on 1) how far up they get on the route (so for example, if someone is able to grab a hold, they would get more points than someone who merely touched the same hold); 2) how many times they fall before they reach the top; and 3) the climber’s overall score over the course of the year. “So there is a chance that someone who has accumulated enough points over the course of the year, who isn’t in the competition, will win the championship?” “Yes, technically, that’s a possibility.”

So it’s not really about that final competition. Nor is it necessarily about getting to the top. In my mind, I revised my initial steps to climbing:

In thinking about the relevance of climbing with instructional design, I think about the differences between behaviorists and constructivists. Behaviorists will look at the wall climbing problem and set a performance objective. For example (and I realize I am giving a quintessential behavioral objective here):

Given climbing shoes, a chalk bag, and a 25ft wall (with designated holds at a 2-spot level), the climber will reach the top of the wall within 20 minutes without falling off once.

If the purpose of the climb is to reach the top, then practice may eventually get you up there. Once you get to the top, you have successfully “mastered the objective.” But this objective doesn’t include the learning that occurs during the process of climbing, which I find is just as, if not more important. For example, positioning your body in different ways to reach a new hold, communicating with others to discuss techniques, or even the motivation to try again once you fall. It would seem like improving on and developing these techniques will more likely prepare you for new climbing routes. I think the same constructivist ideas apply to education.

The problem is, how do we incorporate this concept in academia where semesters and quarters are clearly defined and behavioral objectives are a slave to accountability?