Yesterday, I had an epiphany on my spontaneous 70 mile drive up to Greeley. Typically, I take US-85, but construction signs alerted me to traffic on I-76 going eastbound (off of Exit 216), so I decided to take the route through Loveland: Drive north on 25 until you get to Loveland, drive away from the mountains, and follow the smell, a close friend once told me.

As I passed by American Furniture Warehouse on the right (Exit 219), I began thinking about my typical drive on US-85 and the many visual elements that cued me in on how close I was to arriving in Greeley. I always remember the Starbucks that gave me a Mocha instead of a Latte on the right because I didn’t realize it was a mocha until I was already driving, and I almost threw up in my car. I also remember the place where I had to pull over because I (and the truck behind me) ran over something big, causing the plastic molding under my car to detach. (I ended up duct taping it back onto the bumper.) Then, of course, the tiny Fort Vasquez museum on the left with the cool looking teepee where all the truck drivers weighed their load, and the vigilant police officers hid to catch the reckless drivers who failed to see the speed limit change from 65 to 55. Aya always told me Greeley was 20 minutes from there, but I always knew I was close to my destination when I saw the billboard for my school; the damn billboard on the right that bugged me each time I saw it:

“UNC grads achieve big things.”

(I really hate this billboard. I am certain my school will expel me if I actually added the image directly, but I will provide the link here. I had to laugh when I read, “UNC billboards communicate the university’s key messaging themes through creative headlines and imagery.”)

What big things? What the hell does that even mean?

(I sometimes get emotional during my more or less uneventful journey up north.)

What big thing will I achieve when I write my billion paged research paper?

(I dream of being an Anonymous protester in one of those Guy Fawkes masks, tearing down the billboard in the middle of the night, or a Banksy-type graffiti artist changing the wording so that the ABCDs of the objective were covered.)

As a proponent of clearly defined objectives, as a researcher of higher education, and as a student of Educational Technology, I thought the term, big things, was rather vague. Big things could be a number of things. (What does the school know about my future that I am not aware of?)

Big things could mean money. According to the literature, students with a bachelors degree generally have a higher income than those who only have a high school diploma.

But then, I thought, big things could also be alluding to the rise in student debt: UNC grads achieve big debt.

I chuckled at my thoughts as I passed Exit 228.

Then, I heard Bernard Lavilliers’ 80’s French pop song, “On the Road Again” seeping through my car stereo.

On the road again, again

On the road again, again

Yeah, Bernard (I like to talk aloud, directly to the artists when I am alone in my car), your song is awesome, but why am I on the road again to Greeley when I should be writing Chapter 1 of my dissertation?

On the road again, again

On the road again, again

Lavilliers continued.

(I could be frolicking in the Botanic Garden, drawing inspiration from nature, or visiting Queen Elizabeth at the Denver Art Museum so she can help me brainstorm my research questions.)

Ami sais-tu que les mots d’amour

Voyagent mal de nos jours

Tu partiras encore plus lourd

On the road again, again

On the road again, again

(There is French writing above, but my French isn’t that great, and it doesn’t matter if you don’t understand it.)

And then, it happened.

All of a sudden, I had an epiphany at Exit 235.

I don’t know if you’ve ever had an epiphany before (this was certainly the first of such a kind for me), but my heart started throbbing, and I didn’t know what to do.

Crap. Crap. I need to write this down before I forget.

Should I exit? Should I not?

Pen! Pen! Where is my PEN?

The exit is RIGHT THERE.

I should exit.

No, I may miss Dr. Lohr.

Crap. Kerouac. Kerouac. Beat. Exit.

But you didn’t make an appointment.

Kerouac. Beat Generation. Dharma Bums. On the Road. Neal Cassidy.

But I may miss Dr. Gall.

Dharma Bums. Rolling down a mountain. On the Road. Cassidy. Denver. Objectives. Objectives.

You didn’t make an appointment.

But I need to write this down before I forget. Exit.

Dharma. Road. Neal Cassidy. Kerouac. Objectives. Road. Objectives.

Pen! Pen! Sharpie! Kerouac! EXIT.

YOU DIDN’T MAKE AN APPOINTMENT!

Where is my Sharpie? EXIT NOW. EXIT EXIT EXIT!

My usually quiet Prius screamed as I made a perpendicular turn off of Exit 235 to Starbucks. I ran in, ordered a tall chai, and started furiously writing in my dissertation journal (& doodle book).

Here is an artifact from my bank account that proves I did make this detour in Frederick, CO:

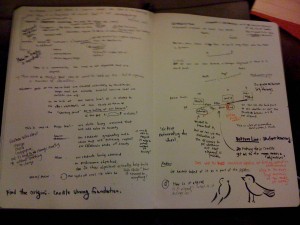

And here is my scribbling from my journal:

Immediately thereafter, I lost my train of thought and started drawing a page of birds.

Luckily, I was able to jot down enough notes for me to review them and organize them into the following thoughts. (I apologize beforehand for some of the awkward grammar, lack of sufficient references, and the unprofessional looking doodles. I am looking for initial feedback to see if I am on the right track.)

Chapter 1 (Pre-Draft)

There are two premises that must be assumed when considering the design and development of instruction. The first premise is that the students (or consumers of higher education) have a valid argument when they question the necessity and value of a college education. The second premise is that the design and development of instruction using a system approach will lead a higher education institution to becoming a successful arbitrator between high school and employment, thereby (if not indirectly) appeasing the concerns brought forward by the first premise.

Premise #1: Concerns about the value of a college education

In the past few years, there have been a growing number of articles inquiring about the value of a college education ([1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]). From the perspective of the students, factors such as the rise in tuition costs resulting in higher student debt as well as the shortage in employment opportunities after graduation, are major considerations that impact their decision to attend a university or community college. From the perspective of the institution, a significant number of students who matriculate must take remedial courses and have low achievement scores when compared to students of other countries. At the same time, a growing number of employers are requiring candidates to hold at least a college diploma to even be considered for an interview. The paradox is that employers screen applicants for the degree itself (even if the degree is unrelated to the job), but criticize universities for producing graduates who have insufficient skills on the job.

The relationship between the economy and education is not a new insight. The famous report by the National Commission on Excellence in Education in 1983 entitled “A Nation at Risk” clearly predicted the same issues. In 1990, the National Center on Education and the Economy echoed the same concerns in “High Skills or Low Wages” and again in 2007 with “Tough Choices or Tough Times.”

The bad economy, layoffs, outsourcing, and job automation as a result of advances in technology are just a few of the realities that students face once they receive their diploma. It is no longer possible to isolate the value of a college education as a stepping stone between high school and employment without taking all of these concerns into consideration. This issue impacts not only the institutional level of planning but also it extends down to the classroom level where the actual learning takes place. In essence, the approach to designing a valuable college education requires designers and developers to consider all related components in its entirety.

Premise #2: Alignment using a system approach to the design and development will lead to success.

The design of a learning environment can be analyzed at three distinct levels.

When planning begins at the micro-level, the focus is on the students taking their courses toward completing their degree. Objectives written at this level are typically delineated on the course syllabus by the instructors (or instructional designers) and passed out at the beginning of the course following approval by the dean.

At the macro-level, the emphasis of the university, as an organization, is on student enrollment and graduation rates by minimizing costs and increasing profit. The discourse on the value of education is often considered at this level.

The focal point of planning at the mega-level (introduced by Roger Kaufman) is to go beyond the needs of an organization and to write objectives that includes external clients. Kaufman begins with an Ideal Vision describing a perfect world; “the kind of world you and your partners want to create together for tomorrow’s child.” In the Mega planning process, elements from the Ideal Vision are converted into an organization’s mega-level objectives. The subordinate macro-level and micro-level objectives become aligned to the mega-level objectives.

Much of the previous literature has looked at the micro- and macro-levels of planning in isolation. For example, books on instructional design has focused on the micro-level, providing a systematic solution to organizing a single course. The obvious limitation is the disconnect between courses, between the course objectives and the objectives of the program or school, and ultimately the succession of courses and future employment opportunities as well as the value an institution adds to society.

When analyzing an educational institution at the mega-level, the emphasis has been to begin assessing the educational framework beyond the organization using a system approach (as opposed to a systems, systematic, or systemic approach). Alignment of objectives among the mega-, macro-, and micro- levels is seen as the key to organizational success.

However, there is one critical element that requires further investigation.

The mega-planning framework is, in essence, a top-down approach which attempts to incorporate the needs of the subordinate tiers by finding a commonality beyond the organization to create a necessary consensus among the different levels. However, in such a model, the needs of the bottom line (the student and their learning) can become obscured. Even the instructor or professor (who is the most knowledgeable in the subject matter, has the closest human interaction with the students and their development, and serves as intermediary between the students and the institution) has very little say in the inclusion of higher-level goals.

To better understand the disconnect it is necessary to theoretically visualize the problem.

A Visual Illustration of the Theoretical Model

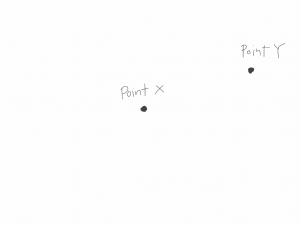

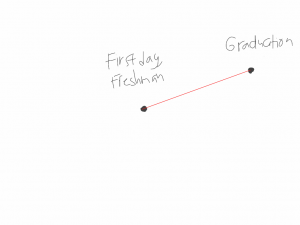

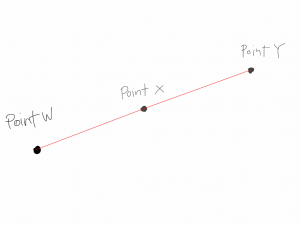

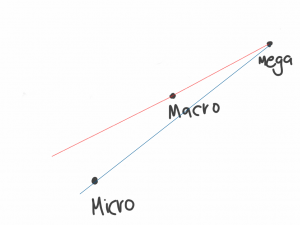

To begin, Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines the word align as the following: “to bring into line or alignment,” whereby a line can be represented by connecting two end points.

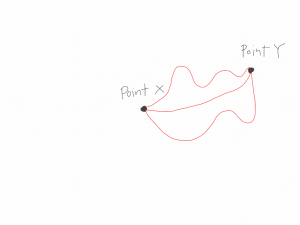

There are many ways to draw a line to connect these endpoints.

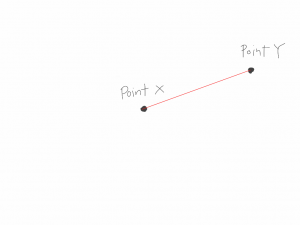

However, the ideal is to find the shortest line.

One can argue that the clarity of this alignment becomes strengthened when a third point is introduced.

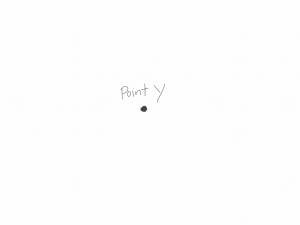

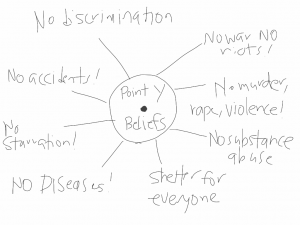

The Mega-planning model uses this concept and begins the alignment process by identifying the societal values of all relevant stakeholders in the educational discourse. First is a point:

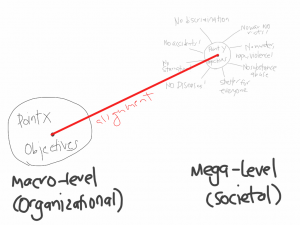

It begins by identifying the ethical beliefs everyone holds and turning them into measurable objectives that relates to the company. (I am only listing some elements from the Ideal Vision from Roger Kaufman’s extensive study.)

Next, the macro-level objectives are created in a way that they become aligned to the mega-level objectives stipulated above.

(When objectives are written in measurable terms, the clarity of the alignment is evidenced in a similar way as a subordinate objective would align to a terminal objective at the micro-level.)

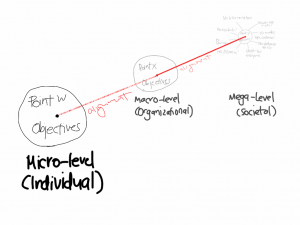

Finally, in the mega-planning process, the micro-level objectives are aligned to the societal and macro-level objectives.

By doing so, everyone has a common mega-level goal that they can pursue.

This is important because all stakeholders begin with a common goal of improving society through a shared vision that is external to the organization.

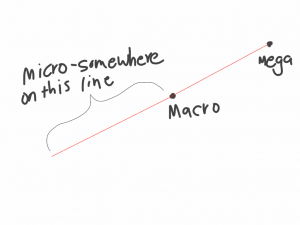

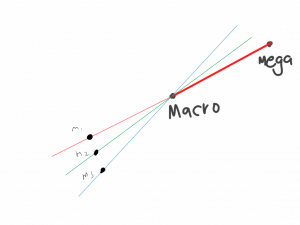

Visually speaking, a problem arises if the alignment between the micro-/macro- line and the macro-/mega- line does not connect.

There is an assumption that micro-level goals will fall at a point on the line extending from the macro- and mega- level goals.

However, one aspect of defining clear and measurable objectives requires the designer to bridge a gap between the current state to the desired state. In other words, the current goals and desired goals must first be identified in order to formulate objectives in measurable terms. Only then is it possible to create realistic and attainable goals. This means that mega-level objectives require knowledge of the initial and desired states of macro-level objectives, and macro-level objectives require the knowledge of the initial and desired states of micro-level objectives. When developing micro-level objectives, instructors must assess the gap between student knowledge, skills, and attitudes carried over from high school to the desired goals of the class. In other words, the quality of mega-level planning is dependent on the the bottom line: what happens in the classroom.

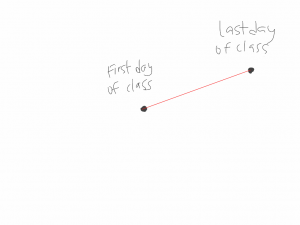

To illustrate what happens at the micro-level, the straight line can represent the most effective and efficient means by which a student can complete a course. The instructor must assess the incoming students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes and continue to adapt lesson content that will reach the objectives.  It can also depict the most effective and efficient means by which a student can complete a degree.

It can also depict the most effective and efficient means by which a student can complete a degree.

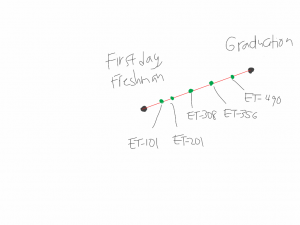

Adding (fictional Ed Tech) course numbers may provide a better visualization of what this means to the learner.

Certainly, the instructors and the department of a program would be the most knowledgable of planning, revising, and making recommendations at this level.

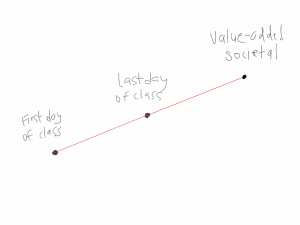

In an ideal setting, if this idea is viewed with the mega-planning (value-added) model described above, the alignment becomes stronger if the extension of the line connects to the value-added point (at the right).

The idea is that there is a smooth transition from the first day of class to the mega-level that includes the student’s ability to find employment and the organization’s ability to help foster an environment that adds value to both internal and external clients. However, the concerns stipulated by the first premise suggests that there seems to be a disconnect.

This problem can be better addressed by comparing the the top-down approach to the bottom-up approach.

In the graphic above, the ideal planning process would be point m1. However, it is certainly possible that the alignment of macro-level and micro-level objectives could be either m2 and m3. This would require adjustments in better planning at the mega-level. Again, what is happening at the micro-level becomes critical in the development of higher-level objectives.

It is certainly possible that it is the macro-level organization that is not in alignment with the micro- (initial) and mega- (desired) levels.

In order to find an appropriate equilibrium among the various level of objectives, there is a need to explore the objectives at the micro-level, not in isolation, but as an essential element of the whole system.

The Course Syllabus

The course syllabus is widely used in college level courses as a means of communication between the instructor and the students. In the past, a syllabus was a single sheet of paper, itemizing the required books and assignments for a particular course. However, it recent years, its function has increasingly gained importance within the classroom. According to Parkes and Harris (2002), the syllabus serves three purposes. First, it serves as a contract between the instructor and the students. Second, it serves as a permanent record. Third, the syllabus can be used as a learning tool.

According to Grunert (1997), the syllabus is a “significant point of interaction” between the instructor and the learners. It is not only one of the first interactions that teachers have with their students (Baecker, 1998), but also, it is a document that “…reflects the instructor’s feelings, attitudes, and beliefs about the subject matter as well as about the students in the class” (Parkes & Harris, 2002, p. 59). Thus, it is a critical tool used by instructors to clearly communicate the goals and expectations of the course and to help support an effective learning environment that aids in student development. This is particularly true in online or self-paced courses where opportunities to create rapport with the students can be limiting.

Among many administrative elements that are described, the course syllabus typically includes objectives as well as lesson activities and assessment procedures. A careful assessment of these three components sheds light on the initial (current) state that is necessary for planning at the mega-level.

For my dissertation committee members and fellow Ed Techies, I propose one big research question:

In examining university course syllabi, how do micro-level objectives of an educational institution, defined as the initial (current) state in the assessment of needs using the Mega-Planning model, help explain the alignment gap in the US education system?

When I think about it, Bernard Lavilliers’ song was alluding to life’s journey where we feel we are always “on the road, again” searching for meaning at junctures that are often delineated by other people. I think Jack Kerouac and the Beat generation would agree. Education is no different. The system has created breaks, whether it is the transition between high school and college or college and employment because it is convenient to stipulate goals when there are clearly defined endpoints, where we can draw straight lines. Unfortunately, for an 18-year old and a 22- year old, this transition isn’t as clear cut and defined as our education system. It is continuous, and we as educators need to make sure we bridge these junctures in a way that smooth but mindful and valuable.

On the road again, again.

On the road again, again.

But, have we taken a look at where are we now, Bernard?